On November 12, 1986, Dale Hansen and his producer, John Sparks, aired a 40-minute special report on ABC Channel 8 revealing that SMU was paying its football players. Despite being on probation, the university had continued giving some of its players thousand-dollar signing bonuses, rent-free apartments, and $750-per-month allowances in some cases. The report led to the cancellation of the school’s 1987 season, the first “death penalty” ever handed down by the NCAA to a major university. In many ways SMU is still trying to recover—even off the field.

I was just sitting in the office, like in one of those old mystery novels: “It was a day, like any other day.” And I got this phone call from a woman at SMU who worked in the athletic department. She said, “Dale, I’ve got a story for you.”

Her tip led us to David Stanley, a kid who had a drug problem and had basically been kicked off the football team. He was trying to sell his story. He tried to sell it to us, and we said, “You know, we don’t pay.” So my biggest concern at that point was, here’s a kid with an agenda. He wanted money. So we had to convince this kid to give us the story without a check attached. And he finally did.

That led to the interview at SMU that has been seen a thousand times. Producer John Sparks and I sat down with Henry Lee Parker, the SMU recruiting coordinator; Bobby Collins, the head coach; and Bob Hitch, SMU’s athletic director. I was concerned they would eventually say we had lied to them about the purpose of the interview—and they did. So I told our photographer, “Push the camera straight down, but leave the recorder on.” It would make them think it was off, which it wasn’t. The picture’s off, but the sound isn’t. It was never going to be used on the air, but I thought we needed the protection, and we did.

I said, “Before we begin, are there any ground rules here? Is there any misunderstanding of what this interview’s about? Because we have some serious questions about your football program.”

Hitch said, “Hell, Dale, ask whatever you want.”

We did. And months later, when Hitch complained to the Times Herald that we had lied to him about the purpose of the interview, I told the Heraldreporter to call Hitch back and tell him I have a recording of our conversation before the interview started and see if he really wants to say that. He didn’t, and Hitch never complained about it again.

Anyway, at the interview, I had an envelope that Stanley said he’d gotten cash in. It was given to him by Parker, the recruiter. It was handwritten on SMU stationery, and it said HLP in the corner, for Henry Lee Parker. But Parker denied it.

When I reached into my pocket and pulled out the envelope—and I hate this every time I see it—I said, “This is hard to do.” I don’t think Mike Wallace would have reached in his pocket and said, “This is hard to do.” But there it was: the smoking gun.

There was a certain empathy I had for Bobby Collins. I had worked with him. I’d worked with Henry Lee Parker. I’d worked with Bob Hitch. They’d always been generous with their time. So I had a certain empathy for the situation that they were about to find themselves in.

The interview wasn’t that contentious. It was along the lines of Henry Lee Parker saying, “No, Dale. That’s not me. I never sent this kid anything.”

But they all knew this wasn’t good. And at one point, Collins stormed out of the interview. I looked over at Hitch, and I asked him, “What is his problem?” And Hitch looked at me and said, “That’s a man who has just seen his entire career flash before his eyes.” That somehow flew right over our heads. I sat there, and I did not pick up on the basic admission. Days went by, and we were sitting in the edit room one night, and I said, “Oh, my gawd! Guys! Guys! Here it is!”

When the word got out that we were working on a story, we started to get a lot of pressure. People in the highest management levels of Belo, which owns the station, had some strong SMU connections. There was some concern that we couldn’t trust our own attorneys because of their SMU connections, so we hired a Washington law firm—a completely independent law firm—to oversee the investigation. We wanted everyone to know how thoroughly we had investigated this and how seriously we took the issue. By then we knew how damaging this was going to be. We were naming names; we were ending careers.

So it came to the broadcast—8:30, 9 o’clock of the night the story aired. And the whole newsroom was on edge. Management was having this big meeting across the street. They said, “We want you to call Henry Lee Parker. We want you to ask him again about his initials on the envelope.”

Here’s the thing: to the satisfaction of the FBI, we had proven that without question Henry Lee Parker had sent that envelope with something in it to David Stanley. David Stanley passed a lie detector test saying it was money, but we had no hard evidence. All Parker had to say to me was, “Dale! I’m glad you called. Thanks for jogging my memory. We sent him a schedule for the upcoming fall.” We would have had to start over.

I had a little cubicle downstairs. My producer, John Sparks, was right over my shoulder. I called Henry Lee Parker. I can almost recite the conversation twenty-some years later. I said, “Henry, this is Dale Hansen. We’re going to go with the story tonight, but before we do, I’m going to ask you again: did you ever send David Stanley anything? Did you send him anything in that envelope?”

And he said, “Nope. Nope. I told you before: I never sent him anything.”

I got off the phone and said, “They’re sticking to this story.” It’s amazing in hindsight. The Washington lawyer just sat there and said, “They still say they sent him nothing? You told him about the lie detector? You told him about the FBI agent?” And I said, “Yeah, yeah, I did. He knows all of it.”

The lawyer and Sparks went back across the street where the meeting with management was going on. But somewhere around 9:30, John came running in, saying, “It’s a go! It’s a go!”

When we got off the air after the special, we were all high-fiving and hugging—but not in celebration. It was relief, just relief after all the tension and the pressure and the build-up.

Then the threats started. I got a huge box delivered to my office. I opened it up, and there was a huge dead bird with a mangled neck. Stuck to its chest was a note that said, “You’re next.”

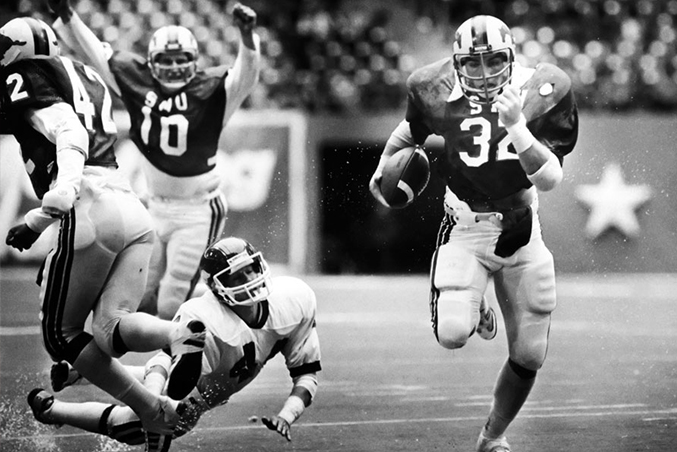

After that, the story just kept growing. A former SMU player told me a year or so later that we’d missed the bigger story. It was gambling, he said. He told me this story: SMU is playing Rice, and one of the big-money boosters comes down to the sideline and tells Bobby Collins, “I need another touchdown.” The score’s like 40 to 7. But he needs another touchdown. So they put Eric Dickerson back in the game. We’re sitting there going, “What the heck? It’s 40 to 7, and now you bring Eric Dickerson back?” And—boom—off he goes. The coaches said afterward, “We did that because we realized he has a chance to set a rushing record, and we wanted to help his Heisman chances.” But, in fact, they put him back in to cover the spread.

I told this story on the radio, and Gil Brandt, the former Cowboys director of player personnel, was at the station that day. Brandt stormed into the studio and started screaming at me: “What the hell?! You irresponsible piece of shit! There’s no truth to that!” He pulled his cellphone out, punched out some numbers, and said, “Here! Talk to him!”

I said, “Who is it?”

Brandt said, “It’s Eric Dickerson.”

So I said, “Hey, Eric. I heard this booster came down onto the sideline and told Bobby Collins to put you back in the game so he could cover the spread. True?”

And he says, “Yeah, that’s true.”

I said, “Here, tell Gil.”

That SMU story changed how I see sports. When I was working in Nebraska, before I came to Dallas, I would go to the Nebraska games wearing a Nebraska sweater and red pants. I was jumping up and down. My photographer used to get madder than hell at me because I’d be jumping up and down, and the camera would shake. I used to genuinely root for the home team. Now I’m cynical about most sports. I had a former Husker player from the early ’70s walk up to me during all this and he said, “You know we were paid at Nebraska, right?”

That story—the good and the bad—God, it was so incredibly exhilarating. I doubt very seriously I’ll ever feel that again. But I hated it. I hated the fact that this story had to be told. And I am incredibly proud that we were the ones who did it and even prouder of the way we did it.

Dale Hansen is the sports anchor for Channel 8.